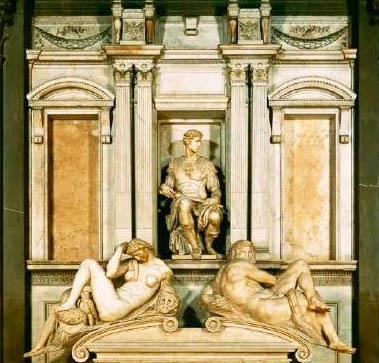

Few spaces in the world boast multiple statues by Michelangelo, but one such location is the Medici Chapel in Florence, which contains seven. The Tomb of Giuliano de’ Medici includes a portrayal of the nobleman as well as the statues named Night and Day. The Tomb of Lorenzo de’ Medici includes statues known as Dawn and Dusk, in addition to a seated Lorenzo. To accompany the tombs, Michelangelo created a seventh statue, the Medici Madonna.

Last fall, the Chapel, located within the Basilica of San Lorenzo, was operating under reduced hours due to the pandemic. It was during those months that scientists and restorers completed a secret experiment. They unleashed grime-eating bacteria on the Michelangelo’s marble masterpieces.

As early as 1595, descriptions of stains and discoloration began to appear in accounts of a sarcophagus in the graceful chapel Michelangelo created as the final resting place of the Medicis. In the ensuing centuries, artists and artisans such as plasterers, would copy the masterpieces, often leaving a bit of grime behind.

Nearly a decade of restorations removed most of the blemishes, but marks on the tomb and other stubborn stains required special and clandestine attention. While the pandemic raged outside, restorers and scientists quietly unleashed microbes that exhibited an enormous appetite, intentionally turning the Chapel into a bacterial buffet. It was also a top secret operation.

The bacteria fed on glue, oil and even the seepage of the poorly buried Medici, eliminating centuries of stains. The operation had its origins in November 2019, when the museum brought in Italy’s National Research Council, which used infrared spectroscopy that revealed calcite, silicate and organic remnants on the sculptures and two tombs that face one another across the Chapel’s new sacristy.

Secrets Revealed in Painting

The study provided a key blueprint allowing biologists to choose the most appropriate bacteria from a collection of nearly 1,000 strains, usually used to break down petroleum in oil spills or to reduce the toxicity of heavy metals. The trick was to find microbes that ate phosphates and proteins, but not the Carrara marble preferred by Michelangelo. The restoration team tested the most promising eight strains on a small rectangle behind the altar. All eight were found to be effective, without being in any way destructive.

The Tomb of Giuliano de’ Medici was the first to be cleaned. Two different bacteria strains were used and proved to be a success. Just as work was to secretly expand, the project was interrupted by the mandatory closure of the Duomo, but when the operation resumed, the results were breathtaking. The centuries of grime are now gone, providing a monumental reason to visit the Medici Chapel and view the statues cleaner than anyone has seen them since the Renaissance.