By David Cavaliere

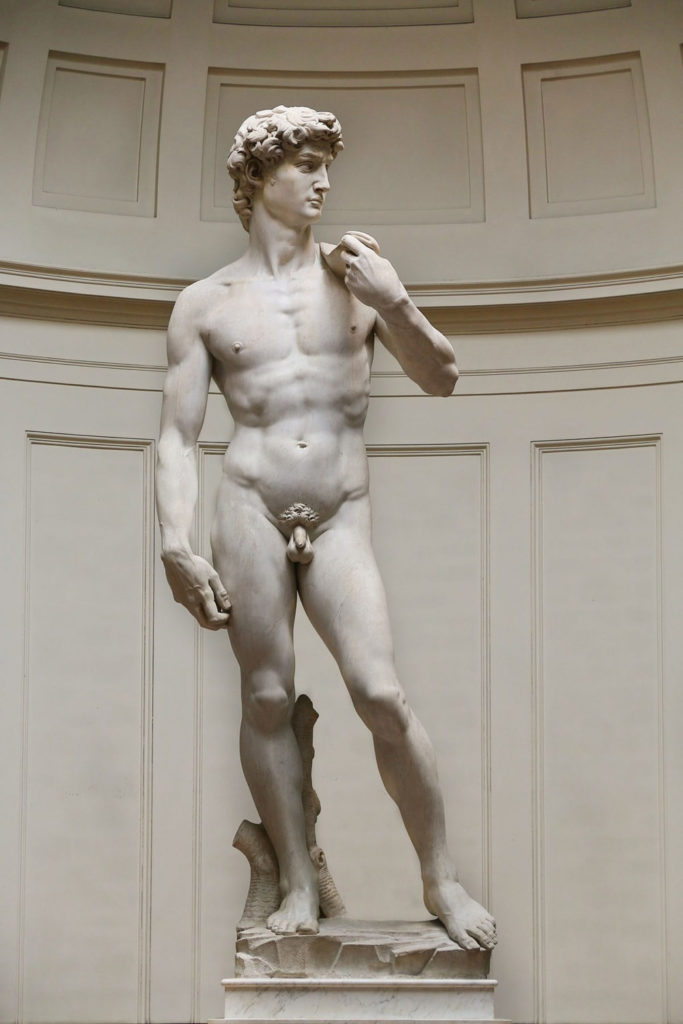

The world’s most famous sculpture is Michelangelo’s ‘The David.’ Viewed by millions each year, standing below the 17 foot-tall statue is awe-inspiring, but the present view of the statue by those visiting the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, Italy, is quite different from the originally envisioned location. The David was first commissioned as one of a series of twelve statues of Biblical figures to be positioned along the roofline at the east end of Florence Cathedral. It was instead placed outside the Palazzo Vecchio. The placement of the statue at ground level not only solved an engineering issue, but sent a political message as well.

Michelangelo had been under the impression that the statue would be placed high above ground level, but the weight of the monumental work, more than 12,000 pounds, was too great to be hoisted to such a height. In January of 1504, a 30-member committee of influential Florentines, including Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli, discussed an alternate location for the massive statue. It soon came down to two locations: outside Palazzo della Signoria, Florence’s town hall, or under the roof of the Loggia dei Lanzi at the Piazza della Signoria. The former was supported by those who favored the Florentine Republic, while the latter location was favored by supporters of the House of Medici, including da Vinci. The great master argued that, due to imperfections in the marble, the statue should be placed under the roof of the Loggia to protect it from the elements. For his part, Botticelli thought it should be placed outside the Duomo, since that was close to the original location intended. His suggestion was quickly dismissed. The former won out and The David was to be placed outside in the Piazza della Signoria.

Moving The David proved cumbersome and it took 40 men four days to haul the figure from Michelangelo’s workshop, a distance of about 2,800 feet. Once there, it replaced Donatello’s bronze sculpture of Judith and Holofernes. Like The David, the Donatello statue also embodied a theme of heroic resistance. The David had a different appearance than it does today. In the summer of 1504, the sling and tree-stump support were gilded and the figure was given a gilded loin-garland in the name of modesty.

The transcripts from the committee’s meetings about the ultimate location were bound in a volume held within the archives of the Duomo, yet these seemed to escape the notice of Renaissance historians until recently. They were read to trace the statue’s provenance, but were never analyzed for any deeper meaning. When evaluating the text against the events occurring in Florence at the time, a previously overlooked conflict fought between the city’s rulers was revealed. It was one in which The David played a small, but important role.

When the statue was revealed to the public, it immediately caused controversy. With the town hall behind him, the hero looked as though he was preparing for battle. His gaze, deliberate or not, was fixed in the direction of Rome, the place to which Florence’s recently deposed rulers, the Medici had fled.

A similar combative vision of The David can be found in the work of another famous Florentine, Niccolò Machiavelli’s book The Prince. Published a generation later in 1532, The David was used as a metaphor for the city-state and personified Florence’s capacity to defend itself.

An unusual feature of The David is that there is no Goliath. It was the first time in artwork that the giant was not portrayed with the much smaller victor. The Florentine republicans satisfied themselves that the reason Michelangelo left out Goliath was that the true enemy of Florence was nowhere to be found. They viewed the Medici’s as Goliath and the statue as a triumph over the family. For his part, Michelangelo had no such intent. He did not show the head of Goliath on the ground beneath the foot of David for a practical reason dating back 35 years before he began to sculpt the masterpiece.

The transcripts from the committee’s meetings about the ultimate location were bound in a volume held within the archives of the Duomo, yet these seemed to escape the notice of Renaissance historians until recently. They were read to trace the statue’s provenance, but were never analyzed for any deeper meaning. When evaluating the text against the events occurring in Florence at the time, a previously overlooked conflict fought between the city’s rulers was revealed. It was one in which The David played a small, but important role.

Backyard Addition

When the statue was revealed to the public, it immediately caused controversy. With the town hall behind him, the hero looked as though he was preparing for battle. His gaze, deliberate or not, was fixed in the direction of Rome, the place to which Florence’s recently deposed rulers, the Medici had fled.

A similar combative vision of The David can be found in the work of another famous Florentine, Niccolò Machiavelli’s book The Prince. Published a generation later in 1532, The David was used as a metaphor for the city-state and personified Florence’s capacity to defend itself.

An unusual feature of The David is that there is no Goliath. It was the first time in artwork that the giant was not portrayed with the much smaller victor. The Florentine republicans satisfied themselves that the reason Michelangelo left out Goliath was that the true enemy of Florence was nowhere to be found. They viewed the Medici’s as Goliath and the statue as a triumph over the family. For his part, Michelangelo had no such intent. He did not show the head of Goliath on the ground beneath the foot of David for a practical reason dating back 35 years before he began to sculpt the masterpiece.