It might seem odd that a seven-foot-tall statue of Christ by Michelangelo would go unnoticed for centuries, but that is what happened to “Risen Christ.” This monumental figure was transferred to a small church about 35 miles from Rome in the 17th century and that fell into oblivion until 1997, when scholars attributed it to the Renaissance master.

Since 1644, it has been located in the San Vincenzo Monastery on the outskirts of Bassano Romano, near Viterbo, but for centuries, the statue was assumed to be an imitation of a Michelangelo’s work.

The statue’s vague origins ultimately helped the monastery to retain the work of art. When Napoleon’s troops invaded Italy at the end of the 18th century, they sacked Bassano Romano, but did not touch the statue. During World War II, the Germans set up a command post in Bassano, but they too ignored the statue. However, since the statue has been finally identified as the long lost work by Michelangelo, the monastery has allowed the statue to travel to exhibitions around the world.

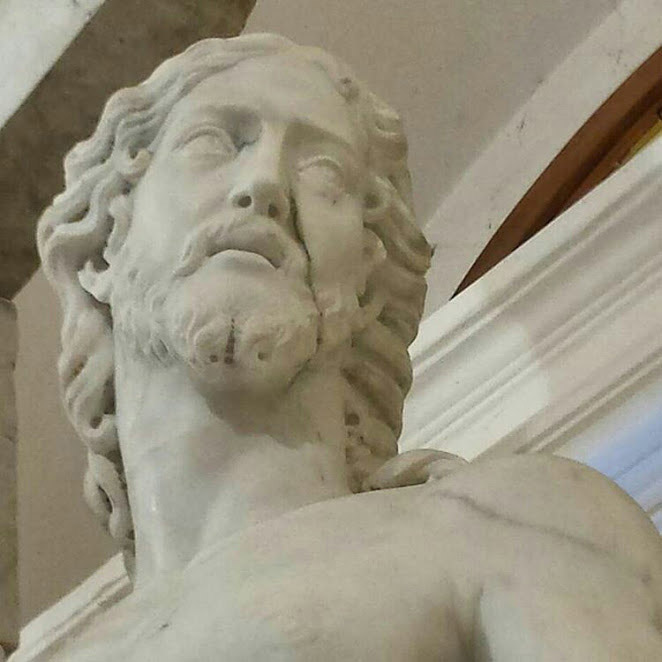

“Risen Christ” was commissioned in 1514 by Metello Vari. When he set to work on a huge block of marble that he had almost finished chiseling out before discovering it had a flaw. The artist tended to work from the feet upward, so he only found the imperfection in the upper part of the block when he’d already created Christ’s body. Michelangelo abandoned work on the statue after finding a deep, black vein cutting through the left cheek. The dark flaw in the white marble runs like a dueling scar across Christ’s face.

In a rage, he abandoned the version completely and got a new block of marble. He returned to Florence and worried about the aborted commission. “I’m dying of anguish,” he wrote to Leonardo Sellaio, a bank agent, in December 1518. Soon after, the artist began a second version of “Risen Christ,” which he completed in 1521. It is this carved masterpiece that stands to this day in the Church of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva, located in the heart of Rome. His abandoned first attempt was forgotten, reworked, and finally ended up in a monastery, where few people have seen it.

Michelangelo also gave Vari the first incomplete statue, which fell into obscurity after Vari’s death in 1554. It was acquired in Rome roughly 50 years later by the Giustiniani family, wealthy collectors who presumably did not know the statue’s genesis. Another artist was commissioned to finish the statue and in 1644, the Christ was transferred to the recently built Church of San Vincenzo Martire in Bassano Romano, where it remained on the main altar until 1979.

The “Risen Christ” was known only from writings describing Michelangelo’s work on a statue. In 1997, Dr. Irene Baldriga and Prof. Silvia Danesi Squarzina of La Sapienza University in Rome, who were working on the Giustiniani archives, tracked down the statue. Since then, the statue has been a “Godsend” for the monastery, bringing many visitors to see this long-forgotten work, which also operates a highly-rated bed and breakfast in part of the enormous monastery complex.

One of the questions that art historians have frequently asked is why Michelangelo was compelled to portray Christ completely naked? It was not out of a desire to blaspheme. On the contrary, this genius – poet, architect and painter as well as the greatest sculptor who has ever lived, was not only a faithful Christian but someone who thought deeply about theology.

It obviously created tensions after the artist’s death. The fact that The Risen Christ in Santa Maria had a bronze covering strategically placed to provide a degree of modesty clearly proves that controversy existed; however, the fundamental reason that Michelangelo could portray a naked Christ was that he was Michelangelo. By the time he created this statue, he had painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling, with all its male nudes and was arguably the most famous artist in the world. The other reason he could portray a naked Christ was that he lived in the remarkable free and experimental culture of the Renaissance.

Michelangelo’s Venetian contemporary Titian in his 1514 painting Noli Me Tangere gives the risen Christ white drapery over his body, obviously the shroud that covered him in death. In Raphael’s last great work, The Transfiguration, the body of Christ is completely swathed in a similar white robe and even Caravaggio in his Supper at Emmaus depicts a well-clad risen Christ. Michelangelo had thought it all through, though. In his left hand, the Risen Christ holds a crumpled shroud. He has consciously decided not to wrap it around himself, or has just removed it. The truth of the Lord’s bodily resurrection is the miracle Michelangelo wants us to see. His Christ has been brought back from death and his body, including its wounds, stands triumphantly alive and before us and it is the genius of Michelangelo gives each of these statues amazing vitality.

Located in just outside Viterbo to the north of Rome, the area is often overlooked by travelers, except for those in the know. For those traveling to Rome, make a note to include a day trip to the area. It will be a fascinating experience.

See our new four part series “In the Shadow of the Divine” detailing the statues of Michelangelo beginning on page _.