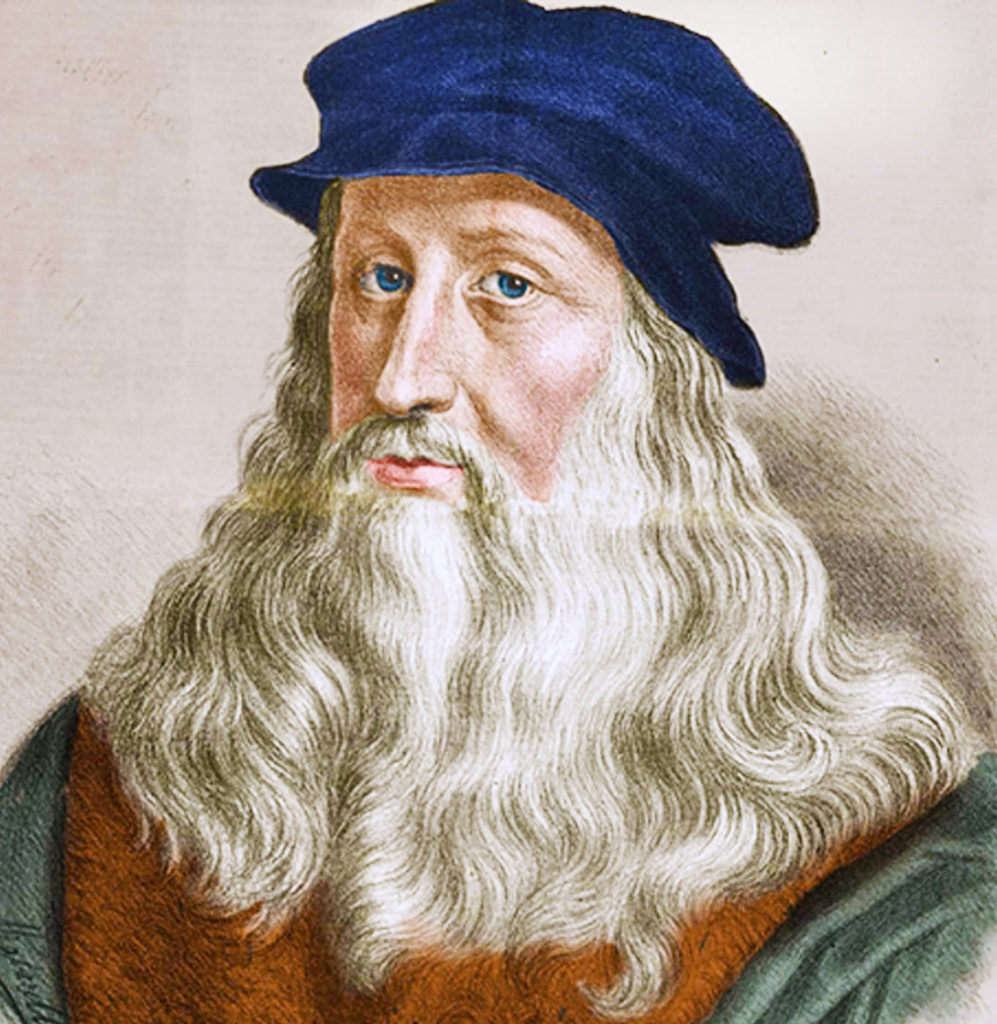

To Leonardo da Vinci, perhaps the most versatile genius the world has ever known, the eye was the key to everything. The man who painted the famous “Mona Lisa” and the “Last Supper” also conceived ingenious machines that anticipated the innovations of designers by hundreds of years. We think of Leonardo today as an artistic genius, but in his time, he was more often thought of by those in power as a military engineering genius.

In 1482, when Leonardo was 30, he left Florence to work for the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza. He had written the Duke a letter describing the diverse things that he could achieve in the fields of engineering and weapon design, while also mentioning as an aside, that he could paint. While working for Sforza, Leonardo offered a whole series of radically new war machines, including an armored car, the first version of a machine gun and an extension ladder, which still looks incredibly modern. One might not think of a ladder as a weapon of war, but in his time, ladders were extremely necessary for scaling walls, an important feature when attacking fortresses.

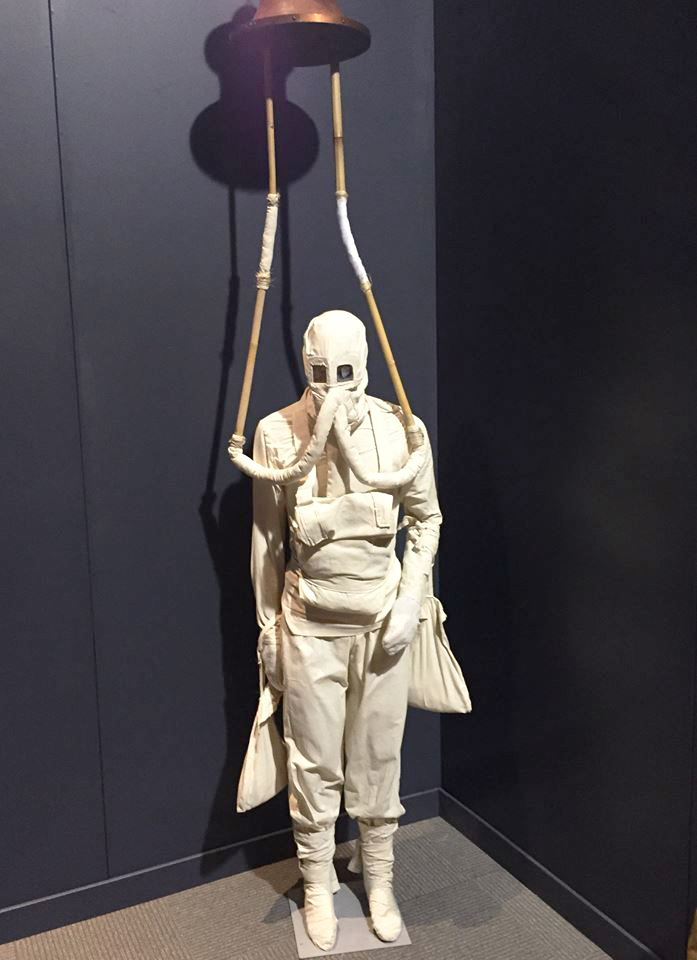

When Sforza was overthrown in 1500, Leonardo fled Milan for Venice, which was at war with the Ottoman Empire. He approached the Senate of the Republic and offered his services as an engineer. Leonardo, always fascinated by the flow of water and its power and wanted to construct a mobile dam that would allow Venetian forces to draw the Turks into the Isonzo River Valley and then flood it, wiping out the enemy forces. He also devised a system of moveable barricades to protect the city from attack. The Senate did not act on his plans, citing the immense cost. He also devised a diving apparatus and wanted to initiate an underwater raid on the Ottoman fleet, drilling holes in the bottoms of their ships. His design was remarkably similar to modern scuba gear. That plan too was not he acted on, but Leonardo was careful to keep the details of his designs secret so they would not fall into the wrong hands.

In Cesena in 1502, Leonardo entered the service of Cesare Borgia, the son of Pope Alexander VI, acting as a military architect and engineer, travelling throughout Italy with his patron. Leonardo first created a map of how to attack Imola, Cesare Borgia’s stronghold. Upon seeing it, Borgia hired him on the spot as his chief military engineer and architect. Leonardo’s journals include a vast number of inventions, both practical and impractical. They also included a mechanical knight, hydraulic pumps, finned mortar shells and even a steam-powered cannon.

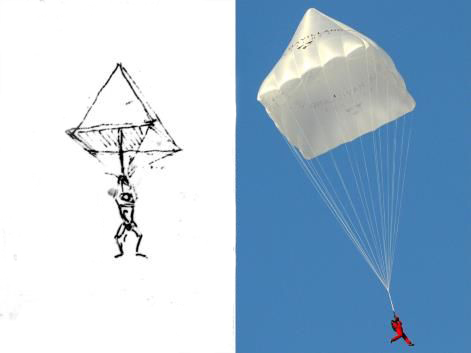

Though credit for the invention of the first practical parachute dates to 1783, Leonardo conceived of the idea hundreds of years earlier. He made a sketch of the invention with this accompanying description, “If a man has a tent made of linen of which the apertures openings have all been stopped and it be twelve braccia (about 23 feet) across and twelve in depth, he will be able to throw himself down from any great height without suffering any injury.” A braccia is roughly two feet.

Like many of his ideas, the invention was never actually built or tested by the genius himself. In 2000, daredevil Adrian Nichols constructed a prototype based on Leonardo’s design and tested it. Despite skepticism from experts, the design worked as intended and Nichols even noted that it had a smoother ride than the modern parachute.

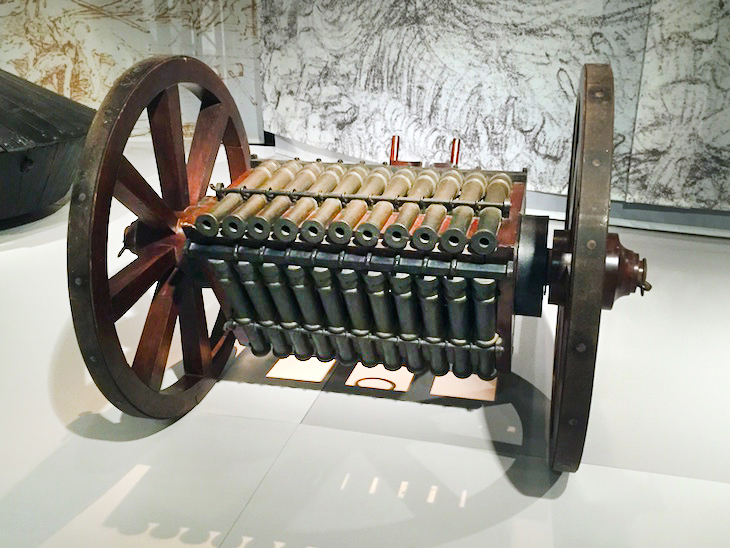

Canons were an important military weapon during Leonardo’s lifetime. The problem that he saw was the time that it took to reload. His solution to that problem was to build multi-barreled guns that could be loaded and fired simultaneously. Leonardo’s 33-barreled organ featured 33 small-caliber guns connected together. The canons were divided into three rows of 11 guns each, all connected to a single revolving platform. Attached to the sides of the platform were large wheels.

All of the guns on the organ would be loaded and then, during battle, the first row of 11 would be fired. The platform would then be rotated to properly aim the next row of canons. The idea was that while one set of canons was being fired, another set would be cooling and the third set could be loaded. This system allowed soldiers to repeatedly fire without interruption. The weapon is referred to as an organ because the rows of canon barrels resemble the pipes of an organ. Leonardo’s design for the 33-barrelled organ is generally regarded as the basis for the modern day machine gun, a weapon that was not developed for commercial use until the 19th century.

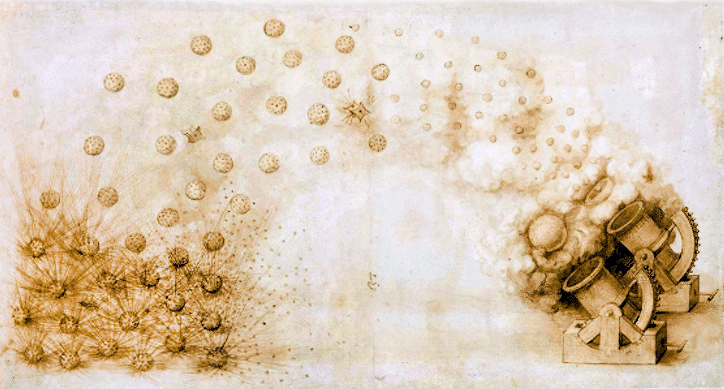

As a military engineer, one of Leonardo’s key beliefs was that mobility was crucial to victory on the battlefield. This idea was found in many of his war inventions. A prime example of this mobile tactical attack is evidenced in his triple barrel canon invention. During the late 15th and early 16th centuries, canons were generally used in stationary defensive position rather than on the battlefield itself. This was due to their weight and the time that each took to reload. Leonardo designed his triple barrel canon to solve both of these problems in the form of a fast and light weapon that could inflict damage on the battlefield. The design featured three thin canons that could be reloaded at once, enabling a greater rate of fire, while the lighter weight and large wheels allowed the gun carriage to be moved around to different areas during battle.

History of the Papal Tiara

The precursor to the modern tank, Leonardo’s armored car was capable of moving in any direction and was equipped with a large number of weapons. The most famous of his war machines, the armored car, was designed to intimidate and scatter an opposing army. The vehicle was designed to have a number of light cannons arranged on a circular platform with wheels that allowed for 360-degree range. The platform would have been covered by a large protective cover, reinforced with metal plates that were slanted to better deflect enemy fire, a concept that was rediscovered during WWII. It also had a sighting turret on top to coordinate the firing of the canons and the steering of the vehicle. The motion of the machine was to be powered by eight men inside of the tank who would constantly turn cranks to spin the wheels.

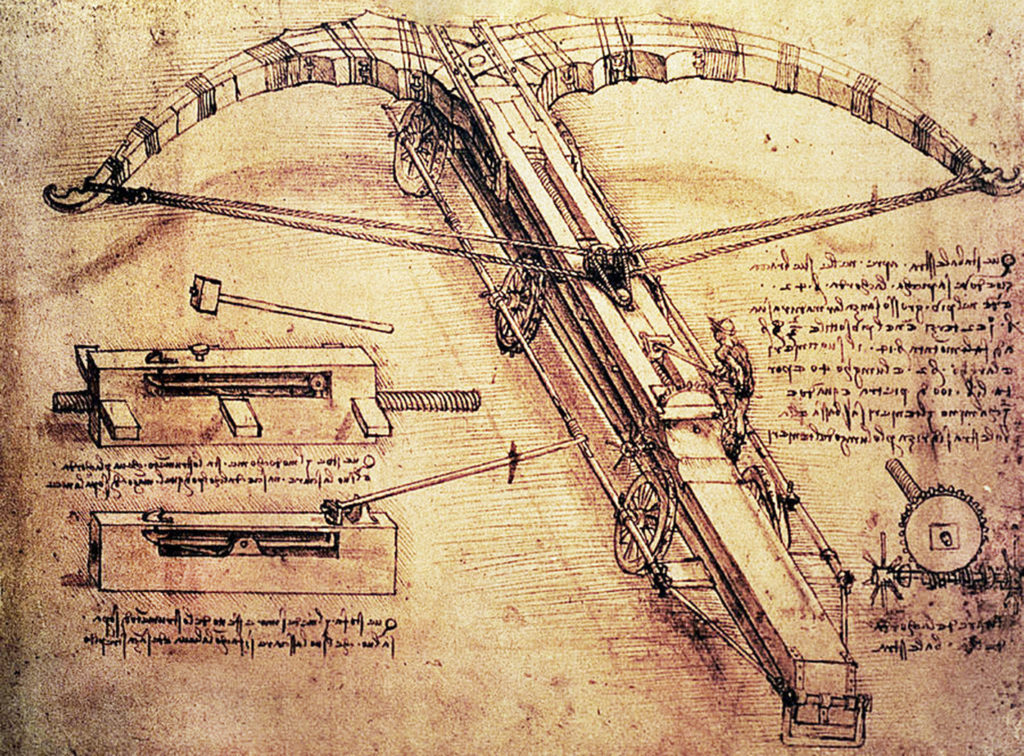

Leonardo also understood the psychological effects of weapons far more so than his contemporaries. He seemed to know instinctively that the fear weapons instill in enemies was just as important as the damage they could actually inflict. This was certainly the idea behind his giant crossbow. Designed for pure intimidation, the crossbow was to measure 80 feet across. The device would have had three wheels on each side for mobility. Rather than firing enormous arrows, the crossbow was designed to hurl flaming bombs. His vivid drawings of the invention also make it clear that the idea behind the impressive weapon was to terrify enemies into fleeing, rather than fighting. Like many of Leonardo’s concepts, it was pure genius.