Roman Emperor Nero is remembered as a villain, but a new exhibition suggests there was more to the ruler than meets the eye. After Nero committed suicide in 68 AD, at the age of 30, a hostile Senate made a concerted effort to suppress any record of his existence. This act of damnatio memoriae, or condemnation of memory, consisted of defacing or destroying images bearing Nero’s likeness and it has made it difficult for the curators of “Nero: The Man Behind the Myth,” a new exhibition that opened at the British Museum in London.

The marble portraits on display in the show are not always what they seem. A bust of Vespasian, who became Emperor in 69 AD after a brief civil war, is actually a re-carved bust of Nero. Small traces on the surface of the marble at the back of the neck indicate where a longer section of hair, a characteristic of Nero, had been removed.

Another marble bust in the exhibition from Rome’s Musei Capitolini, is one of the best known portraits of Nero, the model for how the Emperor was portrayed in the 1951 Hollywood epic “Quo Vadis.” It has recently been determined that only the central part of the face is ancient. Everything else is from a 17th century restoration, which made Nero look rather mean, gluttonous and tyrannical.

The premise of the exhibition is that Nero’s reign, from 54 to 68 AD, was far more accomplished and less tyrannical than historical texts have led us to believe. Stories about his depravity, such as having his mother Agrippina murdered, come from sources that were jealous of imperial power and were written a half century after his death. The primary sources, Tacitus and Suetonius, were members of a senatorial elite that wished to paint the dynasty that ended with Nero in the worst possible light.

The exhibition includes over 200 artifacts contemporary with Nero’s reign, including statues, wall paintings, armor, writing tablets, coins and jewelry. Several of these objects come from new finds made over the last 15 years.

The Invention of the Thermometer

A number of factors weigh in favor of Nero being less of a ruthless tyrant than we have been taught to believe. While slavery was commonplace in the empire, it was Nero who introduced a law that gave slaves the right to file civil complaints against unjust masters. Although he was unpopular with the Roman elite for raising their taxes, he simultaneously lowered the taxes on both the poor and on food imports to make it cheaper for the citizens of Rome. Among the artifacts in the exhibition are several mirror cases with lids that incorporate coins bearing Nero’s image suggesting that many people saw Nero as a positive role model and attempted to fashion themselves in his image.

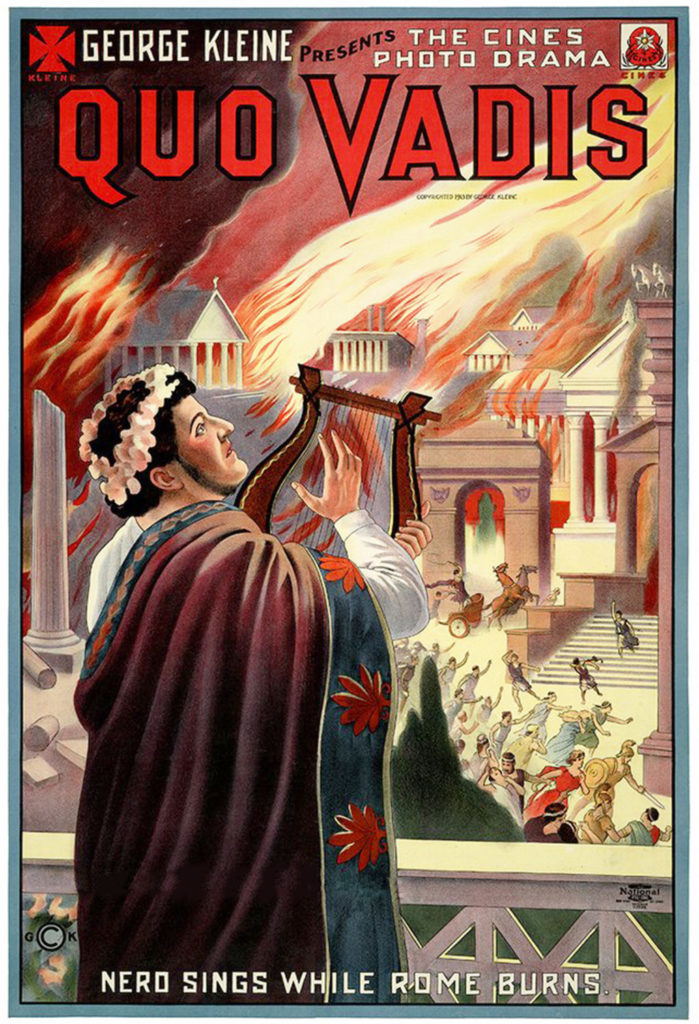

One of the most interesting discoveries may also dispel one of the most common images of the Roman Emperor. It is a coin with Nero’s portrait on one side and a cithara player on the other. It was this type of coin that Suetonius wrote about disparagingly, which led to the symbol of the Emperor’s downfall, alleging that he fiddled while Rome burned during the great fire of 64 AD. A look at the coin under extreme magnification shows that it is not Nero, but the Roman god Apollo who is playing the lyre-like stringed instrument. The lesson of the story is that those who have a narrative to push can effectively do so when they have the right backing behind them. It is a story that sounds very familiar, almost as though it is happening now…