By David Mercaldo, PhD

In association with Cavaliere Aldo Mancusi, founder and curator of The Enrico Caruso Museum of America.

The world of opera has taken an exciting journey through the centuries. This revered and coveted “art form” finds its roots in the culture of the late 1600s. Combining music (known as the aria), lyrics (the libretto), dance, instrumentation, extravagant and often ostentatious costuming, sometimes-bizarre make-up, lavish scenery and the grandeur of magnificent cathedral-like architectures, opera was the perfect entertainment medium to entertain the culturally elite. But these elements alone fall short of telling the story of opera and as for the “cultural elite,” it captured both the mind and heart of individuals at all levels of society.

While opera had centuries of ancestry, it was given a rebirth in the late 1800s with the arrival of the “Italian School” (Verdi, Puccini, Rossini) and with it an Italian tenor who would change the face and voice of opera forever. His name was Enrico Caruso. Born in 1873, in Naples Italy, he would go on to be the most beloved operatic tenor in history and with little debate, the tenor by which all tenors since are judged.

The story of opera and that of Enrico Caruso, would be incomplete without the study of one particular performance found within the operatic masterpiece – “Pagliacci.” Its story begins with a little-known composer. In 1892, Ruggero Leoncavallo (born 1858 in Naples, Italy), penned a two-act musical play that contained one of the most recognizable and beloved songs in the history of music. It is titled “Vesti la Giubba.”*

Operas of the day were presented in one act and the composer’s unconventional two-act format was not met with any enthusiasm. Interestingly, while most works take years to compose, Leoncavallo completed the opera in just five months. It was composed in what historians have come to identify as an emotional “down time” in his life; a passage fueled by frustration, rejection and even ridicule from those in the musical industry. The advent of “Pagliacci,” born out of hurt, anger and bitterness, would change all that.

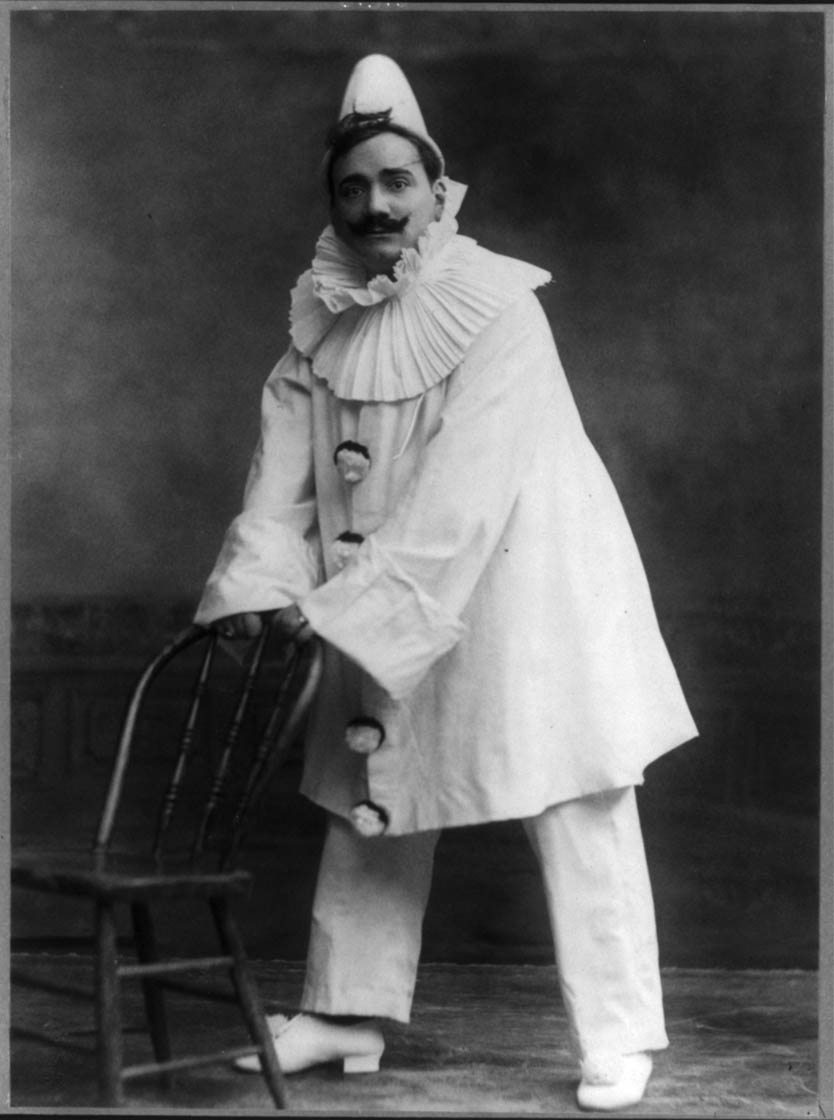

During the latter part of the 19th century, “Pagliacci” was performed to adoring audiences throughout Europe. In 1897, Caruso was cast in the lead role and as the saying goes – that changed everything! Combining the heart-wrenching song, “Vesti La Giubba,” with what was to become Caruso’s signature voicing, the song became one of the most recognizable among all operas ever written. Proof of this was the sale of over one million copies worldwide, recorded by the gifted tenor on the Gramophone label and millions since, on the Victor and RCA label. The song was in fact, the first million-seller.

Caruso’s dramatic and tearful cry in the refrain, “Ridi, Pagliaccio, sul tuo amore infranto,” (Laugh clown at your broken love) found his audiences weeping along. To fully appreciate this magnificent opera is to go to its climax where jealousy, human suffering, revenge and death combine to give the audience a picture of humanity rising up against humanity, in its most tragic and indefensible manifestation…that of murder.

The plot of Pagliacci is quite simple and needs no defense or argument for originality, nor does it bear the suspect of plagiarism, for no composer can copyright the “sins” of mankind. It is a story that has been told since the beginning of time.

The setting is simple. Leoncavallo places four main characters on the stage, a husband, Canio; his wife, Nedda and two men, Silvio and Tonio. Of course there is the usual cast of villagers who complete the cast. The first act opens in Calabria, Italy. It is the story unfolding behind the scenes of the play to be staged where we find the real narrative of Pagliacci.

Tired of Canio’s jealousy, wife Nedda is drawn to Silvio and makes plans to elope with him. Eyewitness to the affair is Tonio, who informs Canio of their plans. The betrayed husband confronts his wife while observing a man disappearing in the distance. Refusing to name her lover, the broken-hearted Canio goes to his dressing room and sings “Vesti La Giubba.” The song paints a picture of the agony of love lost; Caruso captured not only its fundamental musical dynamics…but also its very soul! His performance convinced listeners that he was, for a few moments on stage…Canio.

The primitive recording technology of the day used to document Caruso’s singing of “Vesti La Giubba” did not obscure the inimitable emotion of his performance. The curtain closes on Act One and we leave the distressed Canio in his dressing room, clothed in his clown costume. But the genius of Leoncavallo’s opera is to be found in Act Two, where we learn that it contains a story within a story.

When Act two begins we have the expectation that we are dealing with professionals and that personal problems will not interfere with the integrity of the production. That is not to be! Tormented by his wife’s betrayal, Canio bridges the script and angrily demands, “Tell me his name!” She refuses! The patrons in the audience were unaware that the story on stage now yields to the real life conflict of Canio and his wife. In a moment, fantasy will become reality when Canio stabs his wife Nedda to death; but not before she reveals her lover’s name when she cries out to him for help. Seeing Silvio, Canio kills him with the same dagger. The curtain does not close until Canio tells the audience, “The comedy has ended!” A century ago Enrico Caruso stepped into an obscure operatic character role and sang an aria, “Vesti La Giubba;” when he finished he left a vocal imprint for all eternity.

* Author’s Note: The term has been translated from the morphological study and semantics of the Italian language of the time. But over the centuries, its inferential meaning has instigated continuous dialogue and even debate among aficionados: “Put on the costume” is the simplest transliteration. Yet other meanings can be drawn from the context of the opera’s story. Some might interpret the phrase as an emptying of oneself into a character and costume, if only for a few moments on stage. Is not a theatrical clown one who must hide his true feelings behind a painted smile or a painted tear?